By Jana Wiersema, Features Editor

Question: Who is John Fremont Sleeper?

Answer: He is perhaps one of the least known men in Asbury University’s history, yet one of the most important nevertheless. Without Sleeper, Asbury might never have achieved academic accreditation as early as 1940.

While accreditation may not be a topic most students think about often, it has a major impact on the quality of their college experience and academic life. According to a report by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools’ Council on Accreditation and School Improvement, accreditation:

- Offers more resources to “support and facilitate school improvement.”

- Enables Asbury to transfer credits to and from other accredited institutions.

- Allows students to apply for “federal state grants and scholarships” and “seek admission to military programs, colleges and other postsecondary institutions that require students to come from regionally accredited schools.”

Question: But really — who was John Fremont Sleeper? A president? A provost? An Asbury alumnus?

Answer: He was an atheist and a retired chemistry professor who most likely never set foot on Asbury’s campus. Sleeper lived a good 2,200 miles away from Wilmore, Kentucky, in Santa Barbara, California.

According to an archived article by The Asbury Collegian, Sleeper sent word to several colleges in 1940 that “he desired to give some institution of learning his entire library and scientific collection of a lifetime, upon certain stated conditions.”

Sleeper wrote in his journal that a representative from Asbury, Mr. Householder, planned to visit Sleeper and see the collection on June 3, 1940. (While Sleeper’s entry does not mention Householder’s first name, it is likely that he was referring to Donald H. Householder, an Asbury alumnus who was a student at the same time as Z. T. Johnson, graduated in 1926 and later became the founding pastor of Grace Community Church in Sun Valley, California, according to the church’s website.)

On June 18, 1940, Sleeper wrote, “Asbury College unconditionally accepted the conditions of my Bequest of Collections. I was pleased; but I must admit that I would rather have had Occidental College take the memorial gift because it was less Christian!”

According to a Collegian article from October 26, 1940, Sleeper’s collection included:

- “More than three thousand volumes of books, pamphlets, and periodicals dealing mostly in the field of science, along with many catalogs, newspapers, and manuscripts”

- “Nearly 1,000 specimens of minerals gathered from all parts of the world”

- “A Conchology collection consisting of 15,000 to 20,000 specimens of shell, corals, and fossils gathered from all parts of the world”

- A mineral horseshoe

- A 150-year-old paint box

- An Electrolytic Rack

- A stamp collection

- “A typewriter nearly sixty years old”

- “A telephone outfit of the 1870s said to be the first invented”

- A poison case exhibit

- “A carved black walnut bookcase with three doors having panes of French bevelled plate glass and hand-carved heads … valued at $250 or more”

The article added that Sleeper also gave Asbury a “subsequent donation not in the original gift, the residue of his entire estate, which is to be a unit of the college Endowment Fund, the interest of which is to be used for repairing and keeping in order of this special collection, which will be housed in the library.”

Question: What does this have to do with the university’s first academic accreditation?

Answer: According to “The Story of Asbury College” (a three-volume unpublished memoir by President Z.T. Johnson), Johnson strongly pursued Asbury’s accreditation through the Southern Association while he was vice president under Morrison.

Johnson wrote that the two of the main obstacles to membership were Asbury’s “huge debt and the lack of endowment” and that the college would likely have to close its high school program in order to enter the association (which it did).

Johnson applied for membership in 1939. However, the association found in its inspections that Asbury “had not sufficiently met the standards relative to Faculty salaries, to complete financial stability, to certain Library standards, and other small matters.”

The school was accepted by the association on April 12, 1940, after being verified by the association’s committees as “in a safe and stable condition.”

However, there was still work to be done. A Collegian excerpt included in a July 1940 issue of The Asbury Alumnus noted that “the library is in the process of enlarging its stock of reference works to conform with the list of requirements furnished by the Southern Association” and planned to invest $4,000 in building its collection.

“With the purchase of some five hundred or six hundred different sets of reference works, we are well on the way toward building a model college library,” the article added.

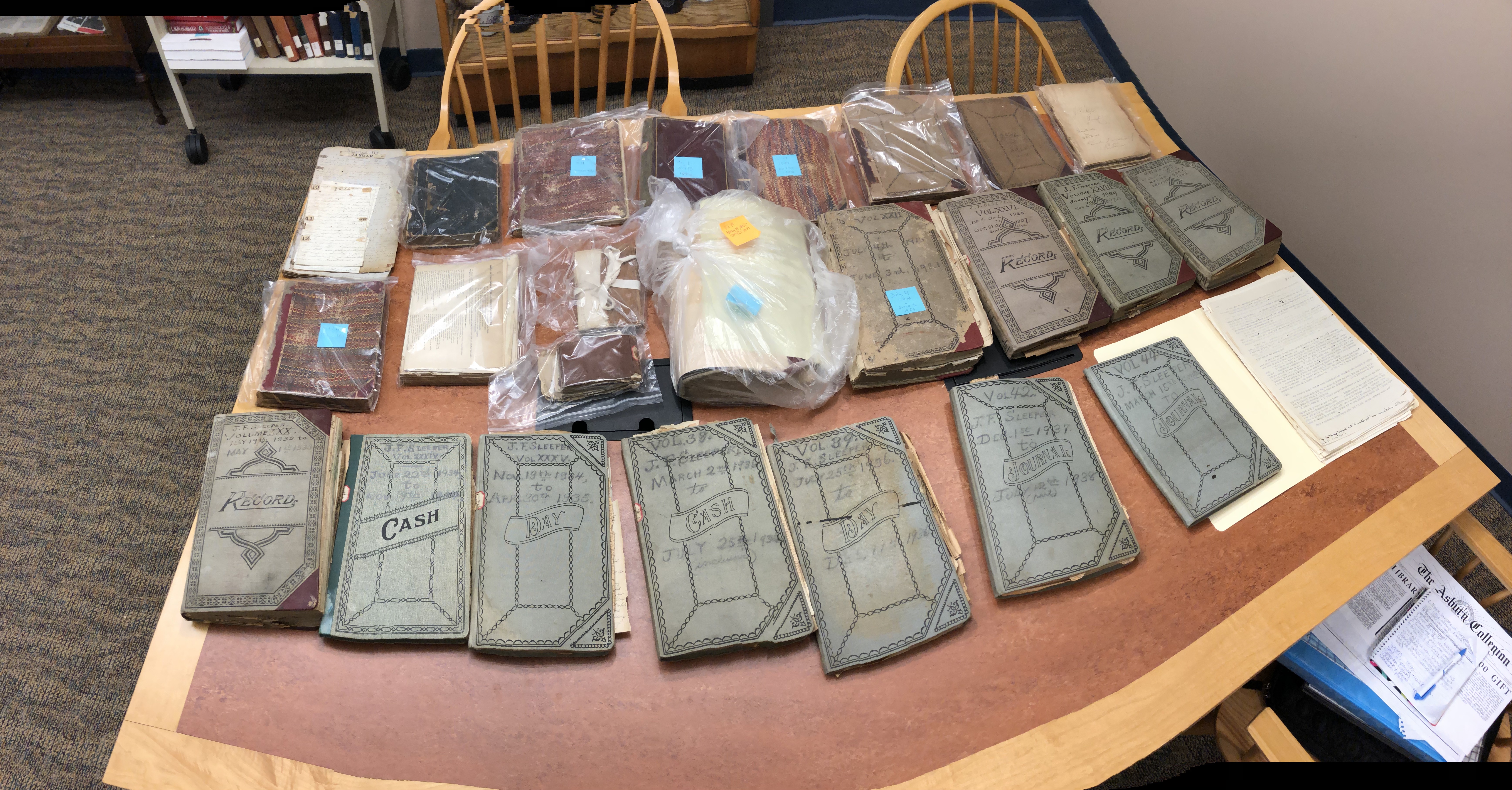

Enter John Fremont Sleeper — who not only donated the items listed above but also more personal materials including (but not limited to):

- His own autobiography

- A biography he wrote about his father, George Washington Sleeper

- Letters to and from Sleeper, his family members and other entities

- An explanation of Sleeper family genealogy

- Sleeper’s journals, which are organized into volumes and span 1876-1940

- A journal of hand-written, original poetry by Sleeper

Question: Why was Sleeper determined to give both his personal and academic documents away?

Answer: According to his journals, Sleeper learned in April of 1939 that he had motor paralysis in his right hand and arm. His doctor also said that if Sleeper didn’t accept the help of an in-home nurse, he would have to be sent to the general hospital.

This was not Sleeper’s only physical affliction; according to his obituary, Sleeper wrote, prior to his death, “I have reached the breaking strain. Because of many illnesses, I would soon be ready for care by strangers. I have suffered agonizing pain for six or seven years.”

It was because of this suffering that Sleeper chose to end his own life in a gas chamber of his own creation in January of 1941. His obituary noted that Sleeper “wrote and mailed a letter to a friend in a local bank explaining he was ending his life by chemicals and warning those who came for his body about the danger of solutions he used.”

According to the police, it was likely Sleeper began the chemical process immediately after mailing his letter. When the police examined his home, they also discovered a tub of ammonia water for neutralizing deadly fumes and instructions on how to do so.

As one might guess from the complex method employed, Sleeper’s decision to end his own life was not a sudden, impulsive act. Several entries in his 1939 journal indicate that he had contemplated suicide before.

In February, he debated suicide with one acquaintance and wrote that “there is a limit to human endurance.” In April, he wrote that he wished he had ended his life with some of his “ready-to-hand poisons” as soon as the effects of motor paralysis began to show themselves.

In 1940, Sleeper began to actively focus on putting his affairs in order. In August, he rejoiced that Asbury had sent him its signed acceptance of his collection.

Sleeper wrote, “One of the great objects to which I cling to life, despite intense pain, to accomplish, at last, after years of effort is consummated!”

Later, after Asbury promised to publish his autobiography in the event that no outside publishing house would, Sleeper likewise wrote, “Now the last great desire of my life is accomplished. … My earthly work and excruciating torments were forever ended!”

In December, Sleeper’s will was finalized, and he remarked, with some certainty, that December 25, 1940, would be his final Christmas day.

In short, Sleeper’s suicide was likely the result of careful planning — as were his actions leading up to his death, including his quest to gift his collection to a worthy college. While his motivations behind this quest aren’t entirely known, I believe he saw the collection as a way to create a legacy — a lasting impression of himself on this earth, as he did not believe in any afterlife.

Question: If this library collection is Sleeper’s legacy, why isn’t it more well-known?

Answer: According to Suzanne Gehring, head of Asbury’s archives and special collections, the boxed papers and artifacts from Sleeper’s collection were moved into Kinlaw Library in 2001 (when the library opened for the first time) and shelved as “unprocessed.”

“The Sleeper items started out on display in the old Morrison-Kenyon Library,” she explained. “But, when Hamann-Ray was built, then the science building seemed like the appropriate place for the rocks and shells to go on display. The books from Sleeper’s personal library became integrated into the main stacks in the library. And the personal papers and correspondence of the Sleeper family that didn’t get processed right away got packed and stored in [Asbury’s] archives. Eventually the story got lost, and this didn’t get rediscovered until 10 or 12 years ago.”

There are also some items from the collection that are either missing or misplaced (such as the black walnut bookcase and the typewriter). Gehring said that this could be due to lack of documentation and/or misunderstanding of certain objects’ values.

When asked why the Sleeper collection’s existence isn’t more well-known, Gehring said it was “lack of curiosity.”

She explained, “It is harder to research primary source materials, so it takes someone who is willing to ‘dig deeper.’”

Since the Sleeper Collection was moved into Kinlaw, it has been studied both by Gehring and by five students (the last of these being myself).

Matthew Kinnell of the class of 2001 worked in the archives after graduating. In 2008, he transcribed the Sleeper family genealogy into printed form, researched the Sleeper and Booth families (who were related through marriage; the latter included John Wilkes Booth himself) and researched written works by both John Fremont Sleeper and his father.

“At that time, the abundance of genealogical information on the Internet was really starting to boom,” Kinnell explained. “I had done quite a bit of personal genealogical research of my own family, and I used the methods I had learned through that process to try to find out who John Sleeper was, where he came from and if he had any family living. To my memory, I did not discover any close relatives surviving. … I searched [the New York Times archives online] and found some information on Sleeper’s uncle, John Clarke, who I believe was an actor in New York. That information led me to his fellow actor Edwin Booth, and then to Clarke’s wife and Edwin’s sister, Asia Booth.”

Kinnell said that the most fascinating part of working with the Sleeper collection was uncovering this family connection. He also once found a letter written after the Lincoln assassination, which explained the troubles the Clark and Booth families suffered “due to their connection to the infamous event.”

However, Kinnell said that one of the less pleasant parts of working with the collection was the portrait of Sleeper’s character that took shape as he read the man’s writing.

“My impression from his journals was that he was quite arrogant,” Kinnell said. “He was an atheist who was very antagonistic to Christians. For that reason, it was a bit surprising that his collection ended up at an institution like Asbury.”

The next student to work on the collection was Ruth Slagle of the class of 2014. Slagle extensively studied and transcribed letters to and from the Booth family and later presented her work at the KLA Academic & Special Libraries Conference. Her work on the collection can be seen at https://www.ruthslagle.net/sleeper-research.html.

Brittany Fischbach of the class of 2016 completed an internship in the library where she transcribed letters between George Washington Sleeper and his estranged daughter, Emma Schumann.

Meg Holt of the class of 2018 encountered the Sleeper collection during her work-study in the archives.

“I sat down and read and typed — over and over and over again,” said Holt. “About 75 percent of my time was spent transcribing and reading his journals, 15 percent transcribing his poems and 10 percent researching cultural things and gathering facts on events he would refer to. … I spent my time investing in the course of a man’s life. Granted, it was someone who had already passed, but when it came time for me to graduate, I was sad because I already missed my work. I still miss Sleeper and pull out my Sleeper files every now and again.”

Holt also created a catalog of Sleeper’s journal volumes and searched his will. She added that if she could time-travel to any era, she’d want to meet him.

“I learned so much about him and wanted so badly to reach through the pages and let him know that he wasn’t alone,” she said, “and some crazy students at Asbury would be very invested in not only his life but himself as well. But what had happened had already happened; there was nothing I could do.”

As for myself, I created a detailed inventory of all of the personal materials in the Sleeper Family Collection, which included suggestions on how to better store, organize and preserve these items. I also created an inventory of student projects, gathered newspaper articles pertaining to Sleeper from an online database, searched President Johnson’s biography and letters and contacted his living kin to see if he kept any personal records pertaining to Sleeper, and acquired a digital copy of Sleeper’s will through a records request.

Sleeper’s will included instructions to bury his body in his family’s burial plot in Jersey City, New Jersey, and the following stipulation regarding his funeral: “No prayers shall be said, nor services rendered by a clergyman of any sect, but an address may be delivered by a Freethinker, or any ordinary individual.”

Sleeper’s will also mentioned his gifts to the university:

- “Any Books, Minerals, Shells, DIARIES, Manuscripts, Letters, Magazines, or Papers of any description found in my cabins, except Books marked ‘To be sold at auction’ are the property of Asbury College, Wilmore, Kentucky, and are to be packed and freighted without charge to that Institution.”

- “From the sum obtained by the sale of my specified Person and Real property: SEVEN THOUSAND DOLLARS IS to be devoted to the publication of my Autobiography. To the Wayside Press of Los Angeles is apportioned $6000 of this sum, and $600 for unforeseen expenses. And to Edwin Rick, of Santa Barbara, $307, and $93 for unforeseen expenses. Whatever is not used of this reserved money, is to be added to the fund to be given as hereinafter stated, to ASBURY COLLEGE.”

- “Should the Wayside Press fail to fulfill its contract, then ASBURY COLLEGE has agreed to publish the autobiography.”

Like Holt, the collection sucked me in from the beginning. And honestly, I didn’t always know what to expect during my work with it. I initially thought I would focus on creating a timeline of both Asbury University and the Sleeper families; I later changed my mind and shifted towards a biographical focus on Sleeper himself; and in the end, my focus has turned to finding the gaps in the story of how the Sleeper Collection came to Asbury and where certain items have gone (though many questions still remain unanswered).

The truth is, I could spend every free hour of my semester reading through Sleeper’s journals and letters and I still wouldn’t feel like I’d scratched the surface of the collection — no matter how much you examine and sort through, there’s always more.

That’s why Asbury needs students who are willing to, as Gehring said, dig deeper into the Sleeper documents and other collections in the archives. It’s too big a job for one person to handle — and, as Kinnell’s and Holt’s stories show, every person brings a different perspective on both Sleeper and his collection. If more students who are drawn to the past and dedicated to preserving personal and historical information continue to work on the Sleeper collection, his legacy will live on.

To be clear, I don’t mean to imply that earthly legacies are permanent. Just like any other physical object, Sleeper’s journals and writings will one day pass away, and no earthly legacy can compare to the security and joy that we find in redemption and salvation.

But even though Sleeper’s eternal fate is out of our hands, we still have a responsibility to study and preserve the materials he left us. Without Sleeper’s generosity, Asbury might not have qualified for accreditation as soon as it did — so we can’t let his memory die, any more than we can forget the presidents and professors that have likewise had an impact on the university.

And through remembering the story of Sleeper — an atheist whose generosity left a lasting impact on a Christian institution — we may also be reminded of an old but true cliché: our Lord works in mysterious ways.